Aunty’s House

An Aboriginal perspective on housing.

Aunty’s House rethinks the spatial planning of medium density residential design to bring community, health and support to the fore. Responding to the broad definition of ‘family’ in Aboriginal communities, this concept facilitates connection and care across households through a layering of spacial zones.

The social stack

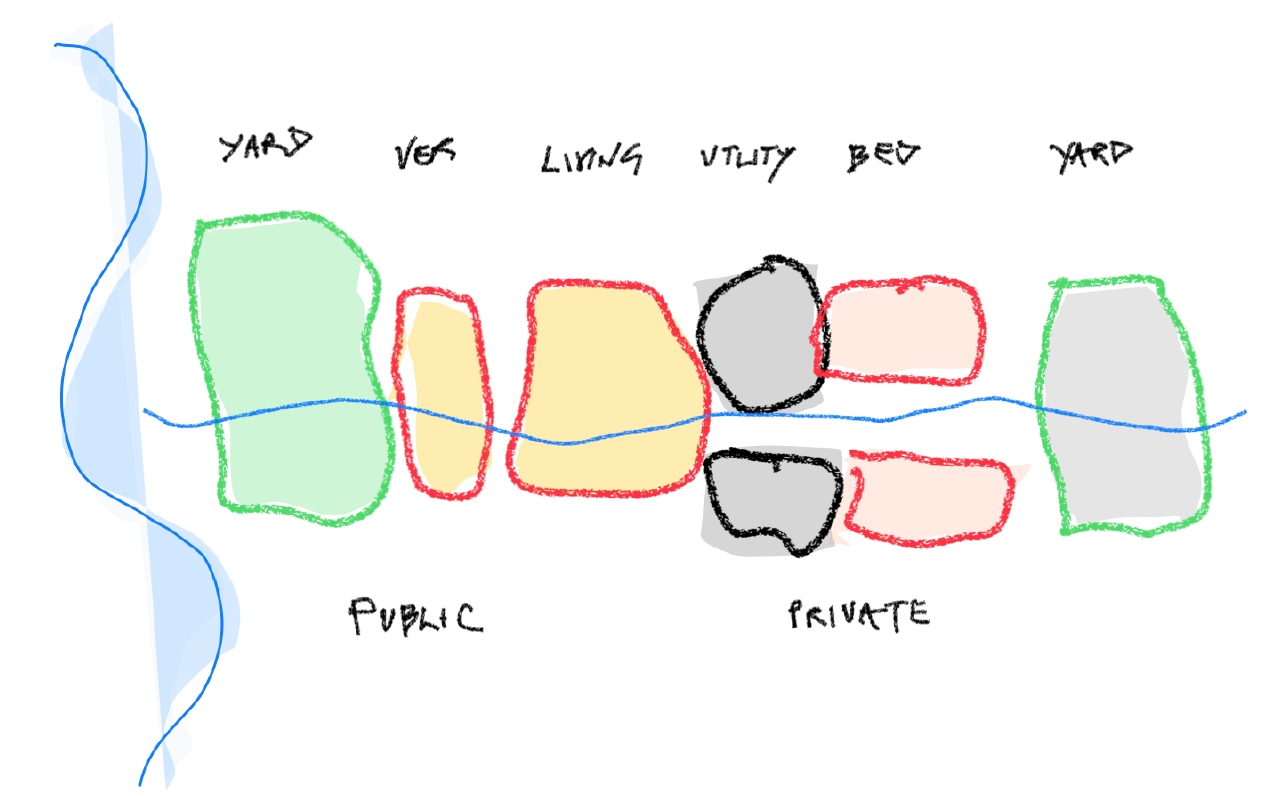

The plan stacks apartments onto five levels, with circulation via a pedestrian path along the front of each level. From the path, each apartment has a verandah that allows varying levels of privacy and openness. Immediately off the verandah is the living space and then the private bedrooms are beyond.

The traditional planning is that of bedrooms and circulation to the south with an entry passing by the bedrooms first to get to the private living spaces and balcony beyond. This however disconnects the living spaces from the public circulations spaces. Social connection is then reliant on active processes only as the bedrooms close off all of the incidental social sparks.

The Indigenous thinking represents a key move that flips the traditional planning model by directly connecting the living spaces and balcony to the ‘social glue’ of circulation spaces.

Typical apartment plan

A layering of public to private zones allows incidental social connections to occur. Mediating different social levels of need for privacy the individual occupant can vary how open their verandah is with re-trackable louvre screens on each veranda. Like the house veranda, the apartment veranda is a passive opportunity to be with others within the context of deliberate public and private socio-spatial planning.

The corner store

This design concept takes the essential hub of suburbia—the corner store—and applies it to the medium-density urban development typology.

At Aunty’s House, the ground floor podium hosts a range of services to support the health and wellbeing of those living in the development as well as the broader community. A women’s health clinic, legal aid centre, community cafe and corner store provide social spaces and support services.

The background story—

Craig Kerslake

In my 20’s my brother and I were compelled to unravel a family secrete. One of shame and cloaked in secrecy. Who really was Ken? Our grandfather was a charming dark skinned man of some mysterious origins. His identity seemed to change over time and after he died at quite a young age he left a shadow of uncertainty and taboo. Something that would never rest well with my curiosity and intrigue.

We travelled to Wellington NSW with a single name which lead us to Auntiy’s house in a heavily Aboriginal populated suburban area. Sitting on her front veranda we spoke of the name ‘Gissell’ to which Aunty told us we should try Dubbo as she thought that name might be from the ‘Mob’ up there.

Aunty told me how she liked to sit on her veranda and after asking what I was studying she told me something that would shape my entire career.

She said something like this -

‘You know, these gubbas [government] make all these houses upside down. Like they are trying to always keep people away from each other. But then they get lonely and nobody cares about each other. They end up living next to each other, but not knowing who their own neighbours are and don’t even care about anyone but themselves.’

Puffs of smoke emerged from a neighbouring hedge. A slender handsome young Wiradjuri boy approached along a broken footpath, cigarette in hand, looking over his shoulder for admiration from some girls across the road. “Johnie-Boy! You come here!”, Aunty commanded. Johnie-Boy froze and respectfully looked at Aunty, came through the gate and stood bracing for sentencing. Aunty took the cigarette from his mouth and sent him on his way.

I asked Aunty if he was a relative and she look strangely at me.

‘We are all Mob, and we are all responsible for for Jonnie-Boy. That’s why I sit out here. To be connected with the river.’

I looked perplexed. There was no river to be seen. I politely asked, ‘What river?’.

‘The river of people going by.’ She said.

Sketching in my little black book I drew spatial plans from what she told me. My traditional thinking of ‘house’ was about to be challenged.

Normally, people seek ‘private open space’ connected to the rear yard with the front yard being incidental, and possibly an inconsequential formality. It was all about the rear yard. A safe place where individual freedom prevails. Aunty told me that this was completely dumb and was the main reason people were disconnected from each other. Also, why, according to Aunty, people lacked responsibility for the environment.

While I sketched, Aunty impatiently reviewed my thinking. The moment I arranged the living room to open up to the front yard her eyes lit up and she poked the page with affirmation. An Aboriginal teenager came in the front gate and sat next to us, waiting for permission to go inside. Aunty waved a finger and in he went. Soon after another arrived with the ritual continuing. Aunty spoke of the ‘People River’, a stream of social interaction. She spoke of how we needed to always be connected to ‘her’.

What occurred to me was that an ancient complex social system was informing what Aunty needed her house to respond to. It was like someone just informed that everything I ever knew about spatial planning was to be thrown out the window.

The upside-down plan